Today’s guest blog is written by Bob Mackintosh who has joined the SAMPHIRE team as a volunteer for the 2014 fieldwork.

I am from Scotland and so the maritime past of the country holds an innate fascination for me. However, after studying law in Glasgow, and realising I wanted to be a maritime archaeologist, went to the University of Southampton to do a master’s in maritime archaeology. I am still there (albeit now living in Edinburgh), working towards a PhD. I chose Southampton for a number of reasons, the programme at Southampton is excellent, and the Centre for Maritime Archaeology is undertaking some excellent research, but I was required to head south as there are now no higher education maritime or underwater archaeology programmes at Scottish universities. Of course I have no regrets about this but it serves to highlight a relative lack of academic capacity in maritime archaeology in Scotland and is indicative of a wider lack of connection with our maritime heritage. Most underwater research is development led, undertaken by commercial organisations and so despite my passion, it is very hard for me to get involved in practical underwater archaeological work in Scotland as a postgraduate student. Heritage, especially when it is under water, can be a challenge to present to amateur archaeologists and the general public in an engaging and meaningful way. This is why Project SAMPHIRE is so important, and is why I jumped at the chance to join it as a volunteer.

My PhD research investigates how the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage is being implemented. The Convention aims to improve the protection of underwater cultural heritage (UCH) through a number of means. These include legal mechanisms such as the prohibition of the commercial exploitation of UCH, and the imposition of sanctions for those acting not in conformity with the Convention. However, just as important are the Convention’s attempts to raise public awareness of UCH and increase the archaeological capacity of ratifying states by making them establish and maintain inventories of UCH, and cooperate in the training of underwater archaeologists.

The UK has not ratified the Convention. However, despite this, many people in the UK work tirelessly to improve the protection of UCH. Project SAMPHIRE is an excellent example of this and a number of its aspects align with those of the Convention, especially the participation of the public in the archaeological process, improving the information about UCH in CANMORE (the national inventory of heritage in Scotland maintained by RCAHMS, and giving experience to early career maritime archaeologists.

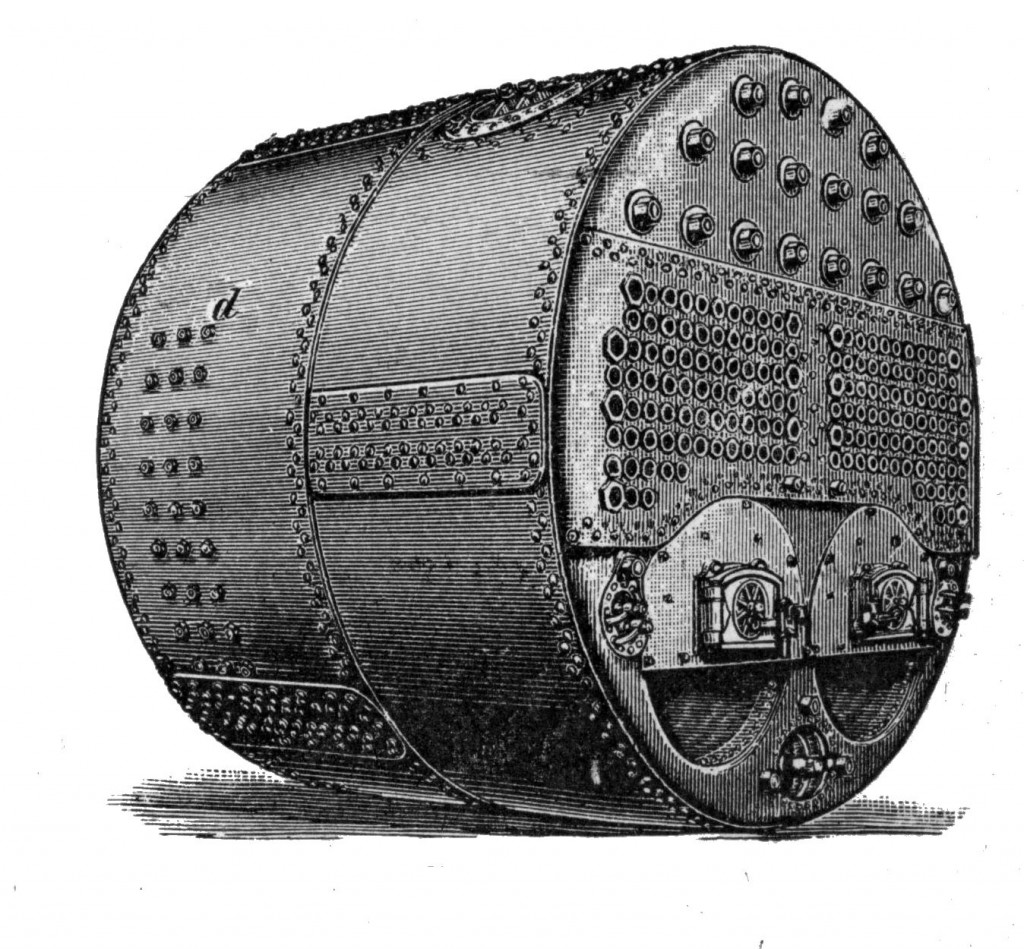

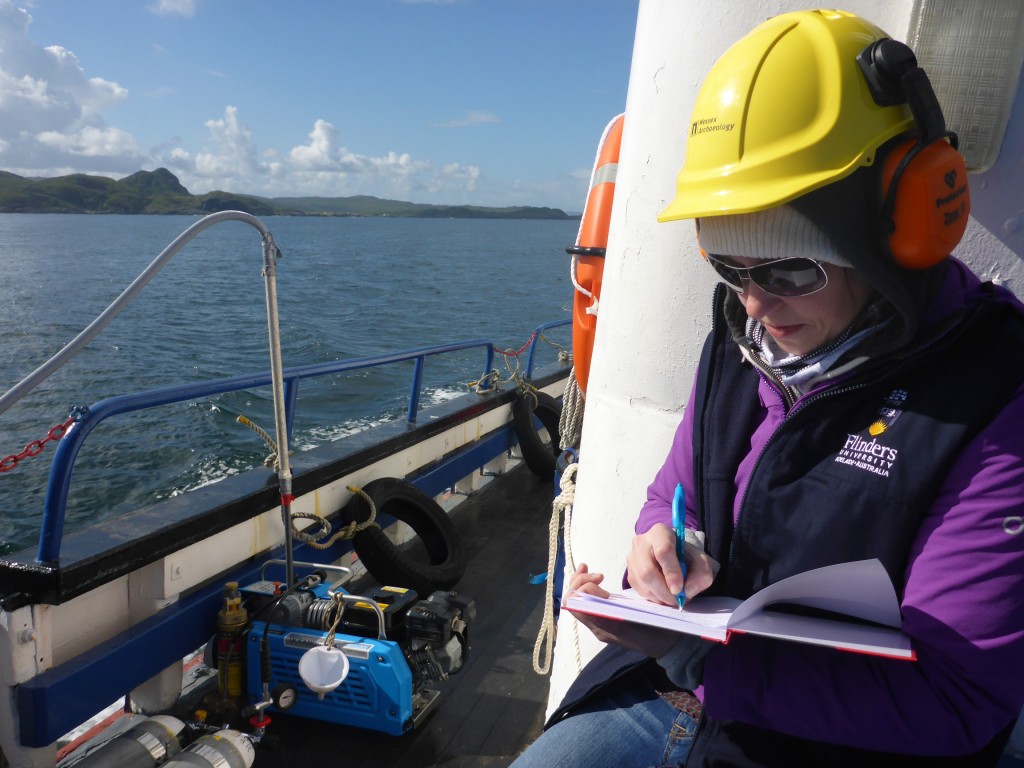

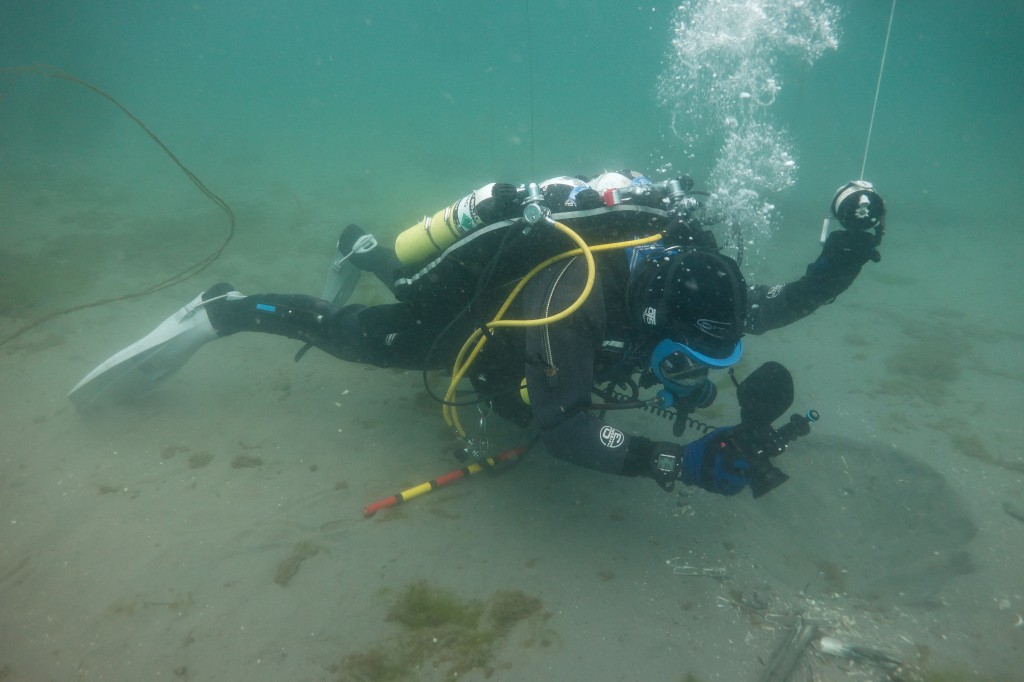

Bob investigates the wreck suspected to be the Iris

Over the past week the team has investigated reports from the public of underwater remains of vessels and aircraft, and in a number of instances the person who made the report has been present to help us work. Tonight we are heading to Lochaline Dive Centre to give a lecture about the project to local dive clubs, who will assist us by diving some possible wrecks sites this weekend. Word of mouth has also raised our profile, our skipper was last night asked in Inverie whether he was the one with a boat full of archaeologists! Our results will be disseminated widely through the annual project reports, project blog/website, various lectures (public and professional) and technical publications to follow. This process does not only help us as archaeologists in encouraging the public to come forward with previously unknown and rumoured sites, but helps engage the communities whose heritage this is. It is a chance to educate people about the importance of their heritage, inform them of the current legal protection it enjoys, and hopefully encourage them to monitor or even further research these sites themselves. A greater public awareness of UCH will hopefully ensure its better protection, and may even eventually lead to a political will for the UK to ratify the UNESCO Convention.

Inventories are key tools for archaeologists, allowing researchers to more easily investigate the maritime past in an area, and if they contain publicly available and accurate positions of UCH, public access is improved and the monitoring of the condition of sites is made easier. This year Project SAMPHIRE has been able to confirm the location of a 19th century wreck on the north-west coast off Skye, thought to be the Iris, identified a ‘Scotch Marine Boiler’ to the south side of Kyle Rhea, and extended the extent of (and added a number of lithics to) a previously known Mesolithic site on Eigg. In all cases accurate locations and photographic evidence will be added to CANMORE. This weekend we are working with local dive clubs to investigate a number of probable wreck sites identified in bathymetry provided by the Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS), hopefully allowing us to add other new sites.

Finally Project SAMPHIRE has included two volunteers on the team, Chelsea Colwell-Pasch and me, giving us invaluable experience of a professional underwater archaeological project and aiding in our professional development. Most importantly for me the trip has provided a rare chance (very rare in Scotland) to participate in scientific archaeological diving, and the benefits to a less experienced archaeologist of diving with professionals from Wessex and Flinders University are incalculable; it is experience I wouldn’t be able to buy.